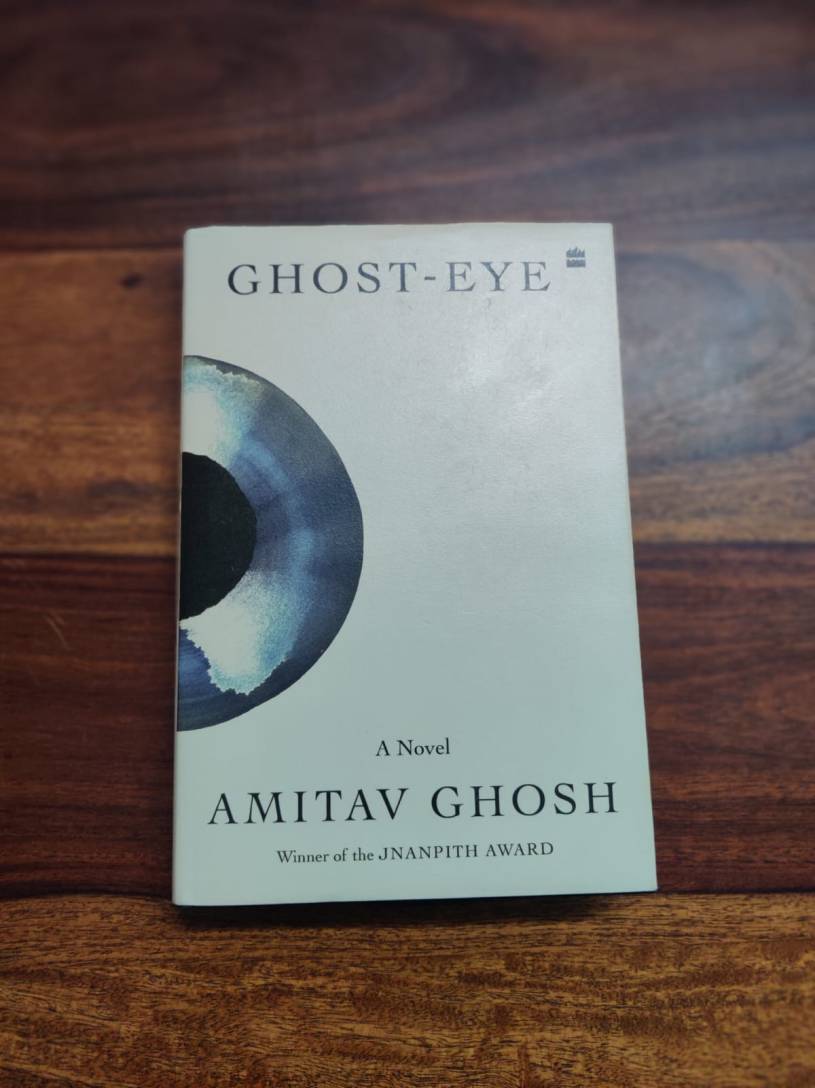

What does it mean to call something “development,” and who gets to decide? I have just finished reading Ghost-Eye by Amitav Ghosh, and I am left with an uneasy void, a strange restlessness, with questions swirling around my head…

I am thinking of the Sundarbans, a place I have not yet visited

I am thinking about the Great Nicobar project, a massive infrastructure plan unfolding in real time

And I wonder what we mean when we say ‘progress’?

Are they the big infrastructure projects? Is it more extraction and mining?

Is it replacing forests with ports and terminals?

Is it widening roads and calling it connectivity?

Is it replacing old cropping systems and techniques?

Is it just technological advancement?

Is it just digital transformation?

What do we really mean when we say right to development and for whom?

Who defines it?

Who benefits from it?

Who pays?

Who gains, who loses?

Given that the novel takes us through time, from 1969 to the pandemic and the present, I revisited the poem that I had penned on World Earth Day amid COVID19: The Long Take

And there it was: crisp, clear skies,

The birds are having a raging party,

Loud, boisterous, incoherent,

Some short and others high-pitched,

The city in full bloom,

With the flowers running a riot,

WhatsApp messages are full of pictures

Of crystal clear water bodies,

The lockdown prompts one,

To gaze outside the window,

Into nothingness,

Yet, amidst the lockdown,

Garbage is catching up on us…

There is a quote in the book: “A lot of stuff that’s being presented as solutions is just rich guys trying to push things down our throats so they can get even richer”. And this is so true: Just look at the amount of make-believe stuff we are told, just so that garbage can magically disappear, from waste to energy plants, to bioplastics and compostable plastics, from plastic to road, and many more.

Garbage apart, what happens to the destruction of cultural heritage, traditional livelihoods, and the identity of local communities?

There is a strange echo in the novel. To borrow from the excerpt, “Past and present collide in a novel that might just be a case of the reincarnation type,” and the back page of the novel says – A story of birth, death, rebirth and the awakening of wonder”.

From the young chid born in a pure vegetarian Marwari family who want to eat fish, to a psychologists testing the memory of past life through culinary experiments, from the spirits that refuse to stay confined, to the lengths of corporate power and greed, from activists who refuse to back down, to the cyclones that constantly remind us of the power of nature, at the core of the novel is the theme of interconnectedness.

It spans life across time (yes, reincarnation), humans and non-humans, body and memory, science and mysticism. Why can’t we explain some things? Why do we instinctively trust laboratory instruments or scientific theory more than embodied memory? Is it because we are too rational? The novel does not preach mysticism. It just asks questions around belief structures. It asks us what we are choosing to forget in the quest to move forward. Have we ever stopped and measured the loss of culture because of large-scale destruction? What happens when plants, rivers, and landscapes are granted agency?

The book nudges you to think. It makes you pause. It makes you question. And it makes you really relook at the words we use – growth, progress, development, and innovation?

What if development has become that bulldozer that moves forward without asking what it is crushing beneath it?

Do we truly understand the enormity of our decisions?

Are some of the solutions simply a louder version of the same problem?